The Grove: a place for remembering

Ray O'Loughlin is a contributing writer for Out Front Colorado.

It began with one man’s vision of a space for contemplation, and happened because a group of his friends labored for seven years to make that vision a reality.

On the edge of downtown Denver, and on the banks of the South Platte River, sits one of just a few memorials in the US — or worldwide — dedicated to those lost to HIV/AIDS. It’s called The Grove, initially inspired by the National AIDS Grove in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

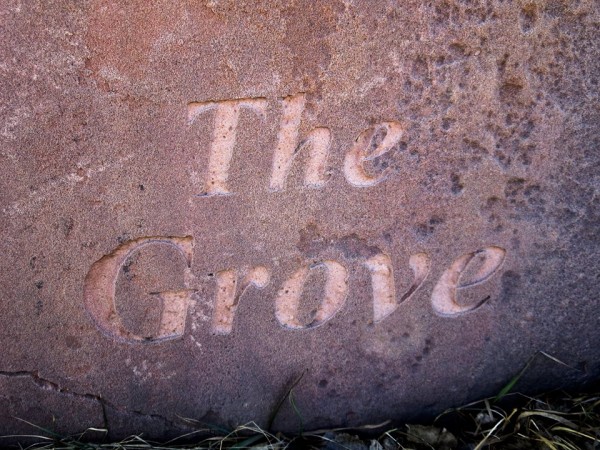

Nestled between the river and Little Raven Street near 15th is an area that is part of Commons Park but is separated from the recreation area. In a small grove of trees, with gravel paths winding through, a brief inscription on a rock tells the story. “This area of Commons Park is dedicated to the remembrance of those who have lost their lives to AIDS and to their loving caregivers who helped them live out those lives with dignity and grace.”

When Doug McNeil saw the AIDS Memorial Grove in California, he asked why his hometown of Denver couldn’t have such a place. Doug died of AIDS in December 1993 at the age of 54. He left behind a group of devoted friends and an idea.

“Doug’s friends got together and agreed they wanted to carry out his dream of getting that done,” says John McNeil, Doug’s brother. “We felt it was sad that there was nothing to commemorate those who had passed on and the many who were ill and dying.”

“Literally on his deathbed, he charged the people around him to get it started,” remembers Al Halverstadt, who was then a neighbor of Doug’s. “We needed a Grove in Denver.”

That band of friends pulled in their friends and incorporated as The Grove Project. In addition to Halverstadt, then rector at St. Barnabas Episcopal church and now retired, Patterson Benero, Mary Blish, Merilou Johnson, Roger Moore, Sen Talley, and Randy Wren joined the organizing committee. None were experienced in local or LGBT community politics; only Moore and Wren were members of the LGBT community.

McNeil and Benero had known each other for years. Both were realtors and very active in supporting Denver’s arts, such as Central City Opera and the Young Adults Symphony. “Doug was very polished and very social,” Patterson says. “He was a lot of fun to be with.”

Wren also remembers McNeil for the good times they shared. “I met him in the late 1980s and we became instant friends. Doug was very witty and had movie star good looks, like Montgomery Clift. He was very sophisticated and gave wonderful dinner parties,” says Wren.

The Grove Project applied for and received a 501c3 non-profit status with the federal IRS. Halverstadt headed the board of directors. They took Doug’s idea to the city’s Department of Parks and Recreation.

Memories differ on the reception they got at the Parks Department. The first site proposed was the lawn on Speer Boulevard behind the Performing Arts Complex. Benero recalls, “I thought it would be interesting with Doug’s background in the arts and theater to have it in [the DCPA’s] backyard. But the city’s reaction was rather stern. Like, how dare you consider that site?”

“They didn’t like the idea of an AIDS memorial right in front of the DCPA because people were there to have a good time, they said, and wouldn’t want to be reminded of AIDS,” Wren says.

“At the time,” says Benero, “AIDS was still a no-no. Why would anyone want to glorify such a thing?”

Halverstadt too recalls the fear of AIDS and even of gay people in the early 1990s. “Funeral directors were refusing to handle the bodies of those with HIV for fear of infection,” he says. “People were afraid that even contact with gays could spread the disease.”

By 1993, Colorado had seen 6,617 cases of HIV/AIDS with 2,473 deaths, according to the Colorado Dept. of Public Health and Environment. At that time, however, most LGBT community energy was diverted to the aftermath and court challenge to the infamous Amendment 2. In 1992, Colorado voters added a provision to the state’s constitution that prohibited any government agency from enacting any protection against discrimination toward lesbians and gay men. That measure was immediately taken into state courts with the Colorado Supreme Court eventually ruling it unconstitutional, followed by the US Supreme Court finally ruling it in violation of the US Constitution. That campaign took four years.

Garnering little community support, Doug’s friends plodded on. Halverstadt remembers Mayor Wellington Webb’s office and staff at the Parks Department being favorable to the idea of The Grove, but claiming the city had no money to build such a space.

The Parks Department proposed another site, this one in a park in southeast Denver. The committee rejected that, since it was remote. A third site was proposed on the north side of town, but that too was rejected.

According to John McNeil, “The city kept changing their minds on a place.”

“We felt it needed to be more in the central city where people with AIDS tended to dwell,” says Halverstadt. “Plus, we feared there might be some neighborhood resistance in the more suburban locations.”

After years of negotiations, somebody — nobody recalls exactly who — suggested the newly planned Commons Park being constructed along the South Platte River.

Organizers liked the idea and took it to the Parks Advisory Board for approval.

“They seemed concerned about approval by the community,” recalls Halverstadt, “but, in the end, decided to take a risk and approved the plan. They wanted to do the decent thing.”

In February 1999, a letter of agreement from The Grove Project board formalized the final plan. “We are delighted that The Grove is an entity in Denver and know that it will be a place enhancing the appeal of Commons Park while offering a site for all to find quiet and comfort,” read the letter drafted by Halverstadt.

He also praised the Parks Department for their cooperation in the project. “Everyone in the Department of Parks and Recreation has been a joy to work with — open, creative, dedicated, and thoughtful.”

That letter also mapped out the vision for The Grove. It described “a grove of trees that would offer the community a quiet space … appealing to any passerby.”

The letter also promised that The Grove Project would provide $10,000 toward the construction. The trustees, Doug’s loyal friends, pitched in much of that amount. Randy Wren, an experienced event producer and publicist, also organized a lavish Valentine’s Day fashion show and dinner to raise funds.

Ruth Murayama, a landscape architect with the Parks Department, designed the area, working with The Grove Project to make the spot “a place for reflection,” she told The Denver Post, which covered the dedication in 2000.

The plan was for a quiet space. “It was to be a contemplative spot, a place to go to remember in an area of historical significance to Denver,” says Wren.

“When people would come into it,” says Halverstadt, “they would be invited by its beauty and peacefulness to reconnect spiritually with those who have gone. It was not to be a picnic spot, but a place to escape busyness.” According to Halverstadt, there was never a plan to list the names of those who had died, since it was not a memorial for individuals.

“It was to be simple and natural,” recalls Benero, “a contemplative place for people who had been touched by AIDS — their families, caregivers, friends.”

Enter the south end of Commons Park from Little Raven Street near 15th, turn to the left, follow a walkway down an incline, and you’ll find yourself in a quiet, recessed area of trees. You’re in The Grove. There are stones meant to serve as benches amidst shrubs and grasses along gravel paths. It has the rustic feel of a High Plains cottonwood grove. The two-acre area stretches down to the banks of the South Platte River. If the river is high, some of the lower area may be marshy. The path winds around and climbs up to the pedestrian bridge over the river.

On Aug. 12, 2000, a small celebration welcomed The Grove. There were prayers, some singing, and a few speeches. Benero remembers herself and others tying dozens of red ribbons on tree limbs in memory of their many friends and relatives lost to AIDS. They quickly ran out of red ribbons. By 2000, the numbers had risen to 8,211 cases of HIV/AIDS in Colorado and 4,394 deaths.

Between 1982 and 2014, there have been 12,698 cases of HIV/AIDS reported in Colorado. Although the death rate has dropped dramatically in recent years, there are still 300–400 new diagnoses reported each year.

What's Your Reaction?

Ray O'Loughlin is a contributing writer for Out Front Colorado.