An Interview with Commando Reveals A Revisionist History of Rap-Metal

Remember Limp Bizkit? Korn? The days of Kid Rock’s rap-metal career? Remember the disaster that was Woodstock ’99? If you answered no to all those questions, either because you’re too young to remember the late-90s or because you—understandably—blocked out that entire cultural moment, allow Commando to provide you with some revisionist history.

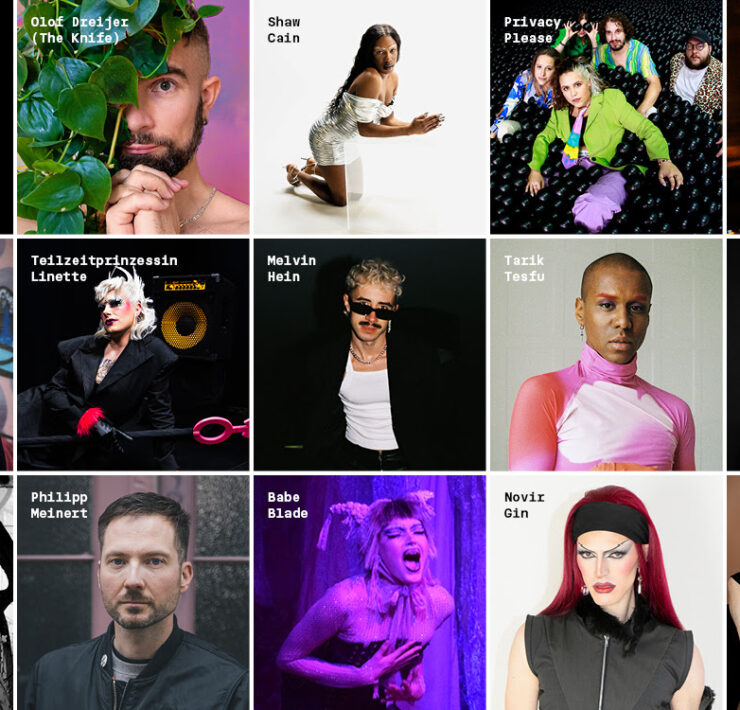

Commando was founded with the idea of reimagining that cultural moment if it was used for good instead of evil and instead birthed a whole new movement where that anger was in service of queerness. From that thought experiment came a punk, metal, hard-rock, rap-rock supergroup featuring queer rapper Juba Kalamka, Tribe 8 frontman Lynn Breedlove, Trap Girl member and Transgress Frest founder Drew Arriola-Sands, RuPaul’s Drag Race star-turned-politician Honey Mahogany, Living Earth Show members Andy Meyerson and Travis Andrews, and performance artist Krylon Superstar.

To learn more about this eclectic collection of artists helming a very unique musical project, OUT FRONT sat down with Juba, Lynn, Drew, Honey, and Andy to talk about the band’s new EP Luggage n’ Umbrage: The Skeebo Sides EP.

You have a lot of different styles mixed together what? What would you say the main influences are particularly on like the new EP?

Andy: This band started around 2016 intentionally as an act of revisionist history. The real question that we had, as we formed–that specific noxious cultural moment that birthed nu metal where Clear Channel [now iHeartMedia] started buying all the radio stations, and then they went all in on Limp Bizkit, and Staind, and Korn, and they bet on the wrong horse, and that horse was just insane–imagining if that specific cultural moment had been used for good instead of evil, how would the world have been different?

And there were several iterations of the vocal lineup. It started with Krylon Superstar, Christeene, and Big Dipper. And then for our first proper album, we morphed into a configuration where the two quarterbacks at the helm of the project to start where Lynee and Juba and each of them then we’re wanting to bring in the folks they were most inspired by [and] most wanted to collaborate with [and] work with to fill out what became a core of lead singers for the first album. And that was where Honey and Drew also came into the project. We wrote before we knew each other, and so we tried to write a bunch of things and take them to the studio and see what happened. And over the course of that process, we became a band, and a real family in a way that was exciting.

But we also had too many songs in that process. So this EP was created during the sessions where we first started to record and write and make stuff together. Each singer quarterbacked their own songs. But this EP came out of those sessions with Juba because, once we started writing with Juba, we couldn’t really stop. But it’s a vestige of that specific time in the band process when we were operating as if it was almost five different bands that had to coexist as one. Juba was the only singer on that EP, whereas now when we’re making anything, it’s hard to imagine it not being this collaborative soup.

Juba: If you’re talking about the influences in the genesis of that, at the same time that Andy was listening to those records– around the mid-to late-90s–I had stopped listening to records and stopped performing between like 1995 to 2000 because I came out. I had been doing hip-hop for years and just hadn’t really found a space where I ended up doing queer hip-hop stuff yet on a regular basis. So I pointedly was familiar with Korn and Limp Bizkit, because they were so ubiquitous, but I was trying not to listen to those records in particular. I just had my visceral annoyance with them. But when I met Andy and Travis, when they came up with that idea and told me what they were trying to do, I went back and listened to those records and begrudgingly had to admit that I understood what they meant to Andy. I was like, “Okay, I can hear why he was into this”

I want to expand on something you’re already talking about, which was that moment of rap-metal in the late ‘90s and into the early 2000s. I always say there’s definitely some merit in early Limp Bizkit, but I feel like that third Limp Biscuit album, Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavored Water, was, I argue, one of the worst things I’ve ever heard. And I think that that just tanked the entire genre and the idea of rap-rock became a joke. And I think that’s unfair because that combination is a great idea. It was just done in a very public, big way very badly. Do you think that it’s tough to be that kind of band right now?

Lynee: Andy sold me on the idea of taking a genre and twisting it on its head queering it. Because that’s what I’ve always done as well. And the way that he put it was “Who has more of a right to rage than us? Those guys, bunch of white dudes, they don’t have a right to rage, we have a right to rage.”

Andy: There was the agenda in the beginning, for sure. It was about, who has agency over being loud, or being aggressive, or feeling angry and creating music about that. But also, as time goes on, enough time has passed for Limp Bizkit to be irrelevant in the cultural conversation. The synthesis of rap and rock does not belong to that era and does not belong to those bands. There are decades before and the decades following [which] have all incorporated those elements in different kinds of ways.

Are there any challenges that you face or prejudices that you face as a band that is in the rock sphere that is focused on queerness and diversity?

Honey: Well, we have played a lot of very queer gigs. And certainly, there’s a lot of space within queer music, queer festivals, performing with other queer bands, where we have not put ourselves in a position where we might experience some of that. Even when he played South by Southwest, for example, it was at Cheer Up Charlie’s, which is a queer venue. And so I don’t think that we have been in a position where we’ve played with all straight bands that I can remember. Being based in California, and specifically in San Francisco/LA, it’s just a different environment. That doesn’t mean that toxic masculinity doesn’t exist in these cities. But, just given the range of things that we’ve played, we’ve been fortunate not to come up against that. Yet.

Lynne: I think the beauty of what we’re doing now by playing a lot of queer and trans-friendly shows is that we are building an audience. And when we do that, we’re building power. And by the time we start playing those bigger shows, when we hit Coachella, watch out motherfucker. When the audience feels empowered by what you’re doing, if there’s some asshole out there, they ain’t gonna say shit. They’re not even gonna follow you outside because they know that you got a posse.

Juba: But I think that there’s a space like Honey is talking about San Francisco, California, the Bay Area, that we get to be who we are because there’s a way that we have been supported and nourished in a particular way by this space as a base. And we carry that with us where we are. And not necessarily fearlessness, because it’s not pretending that there isn’t vigilance as a context of me moving through spaces. I got a crew, but I’m still black, I’m still queer, I’m still in the world. I get that, too, there’s a way that we take for granted the way that we confidently move. All of us have been doing this for a long time. But there’s also a way that we confidently move through space that just people either are not able to do or do not have the support to do that I think resonates in a particular kind of way.

So you talk about how you haven’t been doing this a long time, but you ended up on Kill Rock Stars, which is a legendary label. How’s that experience been working with them?

Andy: They’re great. And super sweet. The thing I’d say about us, we haven’t been a band super long but we’ve all been professional musicians for an extremely long time. I think Kill Rock Stars worked with Lynnee in Tribe 8 back in the day. We’re in a funny, weird space that’s actually really fun because we get to do something new, but really we’ve all done enough that there’s a context for the work we’re doing. And there’s no one I’d rather be working with than Kill Rock Stars on this for sure.

Juba: Yeah, that’s been amazing for me, spending a long time having critical success with a lot of self-released boutique products, and the dynamics of having a label having the reach of Kill Rock Stars coupled with the credibility and the legacy. One of my co-workers [was] asking about when the EP was coming out. And he’s like, “Oh, so Kill Rock Stars? Wow, Juba, you’re not just gay famous, you’re regular famous.”

What’s next for Commando? What are you working on next?

Drew: We have an album that we’re working on. We’ve been writing it this year. And we’re going to start recording as well and we’re doing shows. We’ve been getting together maybe every month to write. Each one of us has a lot of songs, more than an EP’s worth of songs. The second album’s going to be even crazier than the first one.

What's Your Reaction?

Julie River is a Denver transplant originally from Warwick, Rhode Island. She's an out and proud transgender lesbian. She's a freelance writer, copy editor, and associate editor for OUT FRONT. She's a long-time slam poet who has been on 10 different slam poetry slam teams, including three times as a member of the Denver Mercury Cafe slam team.